The night I saw Corso in a dim Bohemian bar in New Brunswick, NJ sometime in the 80's (1983?) I was with two buddies

from graduate school. We had just come from a class with Nathaniel Tarn on modern poetry, and I had

convinced my friends to come with me. They didn't know what to expect. I kind of did, and I was

excited; but first we had to stand and listen to two or three young Beat wanna-be's deliver their loud

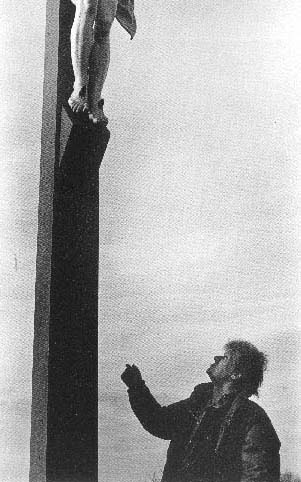

insistent clanging rants, and then Corso stood up and walked over to the microphone. He was short and

missing some teeth and his face looked like an old boxer's. I liked him immediately, and when he began

reading it was obvious from the start that, unlike the previous readers, he was a poet. I don't remember

what poem he read first , but it was a seamless combination of sound, image and insight and every once

in a while there was a line that made me laugh out loud. The poet pugilist was funny, but he was also

a little scary: his mannerisms were erratic, almost frenetic, and I think many of the 20 or so people

in the bar stifled their laughs because nobody knew how he might react. I laughed half-expecting

him to drop his book and take two steps into the audience and punch me in the mouth. But the poem

"Marriage" was the first poem that made me laugh and cry and here I was standing ten feet away from

Gregory Corso, the aging boxer who had had a face lift and seemed to be wearing a wig, or if it was his real

hair it had grown long and had been dyed an off-reddish color that didn't look quite real. There was also an

angularity to his face that, combined with the wig, made me think of an old transvestite, or at least a

woman in a man's face. Maybe a satyr. The again satyr read on, one good poem after another, and then I noticed

something strange : he wasn't finishing any of his poems! Instead, every time he got close to finishing a

poem his voice would trail off and he would mumble something, pause and look down, and then

introduce or just start reading the next poem. It was a strange tick and he seemed to know it, that

not finishing his poems was bizarre, and he started to get increasingly more self-conscious about it;

until at one point he finally said, "I can't finish this poem," or something to that effect, and then, "I can't

read the last lines of any of these poems and I don't know why." When he said that, I was standing right in

front of him, and it sounded as if he wasn't being rhetorical but he were asking, almost pleading, for an answer,

so without thinking ("first thought, best thought") I said , "Because you don't want to die." And then

Corso the poet looked at me and shrugged and kind of chortled or snickered, I couldn't tell which but I kind

of ducked, and then he looked back down into his book and started reading another poem, which was as

good as the previous ones. But he didn't read the last line of that poem, either.

Monday, February 24, 2014

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)