I am Huncke's literary executor. Roger is now dead but his wife

Irvyne is alive and I can ask for more specifics.

One thing I do remember when I was with my son in Roger's used book

store called the Rare Book Room -- Huncke was there, Roger, Gregory,

James Rasin, myself -- many people -- maybe Marty Matz, I'm not sure

if he was in town that day or not -- in any case my son was about 20

months old -- good looking face, very open with everyone -- good grass

and good whiskey -- anything anybody would have wanted was there

including great literature -- and when Corso met my boy for the first

time he picked up a magic marker and wrote YES across his forehead.

Later in the afternon turned to evening he did a portrait of my son on

the back of a letter off of Rodger's desk and I still have the

drawing.

All the best,

Jerome Poynton

Wednesday, September 1, 2010

Tuesday, April 27, 2010

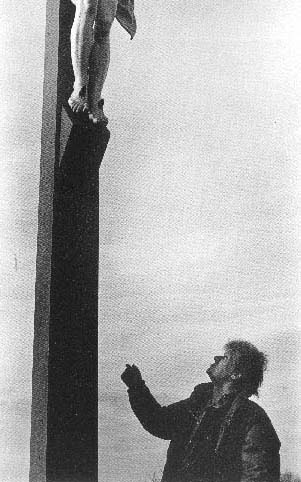

Photograph of Corso's Grave by Dennis Formento

Friday, March 26, 2010

Corso, by Gerald Nicosia

I knew Gregory Corso over a 24 year period, and have so many memories that sometimes I think I should write a book about him. In fact, Gregory was always mad that I had written Kerouac’s biography and not his. He used to say in his Greenwich Village bad boy’s voice: “I got one thing against you, man … you went for the dead one, man. You didn’t come for the living one”—meaning himself.

Gregory often pretended to be mean; and sometimes, drunk on vodka, he could truly be one of the meanest people you ever met. If you had a big nose, he could (drunk on vodka) spend an hour finding 5,000 brilliant poetic ways to make fun of your big nose. I have seen many people, men and women, leave a room in tears because they could not bear Gregory’s relentless, incisive jabbing at all their weak points. The more he saw you were hurting, the more he’d keep after you—till he got a response, the response he wanted. If you simply came back and said, “Aw Gregory, you’re just full of shit,” he’d probably smile and leave you alone for the rest of the night—depending on how much vodka he’d drunk. There were some nights when he simply wouldn’t quit, when a kind of animal anger in him just kept burning at white hot heat, and those nights it was better to leave him alone. The next morning he’d be all smiles, ask you to have coffee with him, and by the way, could you lend him twenty dollars?

But there was a big, real heart inside Gregory Corso. In the things that mattered, he did not fool around. I will never forget that when Jan Kerouac was banned from speaking at NYU in 1995, at a conference about her own father (Jack Kerouac), because the Sampases had cut a deal with Helen Kelly, the NYU programs director, almost all the Beats turned their backs on her. It was simple: Sampas had (still has) a major connection with Viking Penguin, where most of the Beats were or wanted to get published. A petition went round for Jan’s right to speak at the conference, but most of the Beats wouldn’t touch it, fearing to lose their upcoming Viking Penguin contract. Gregory Corso (along with Ed Sanders) was the only Beat who signed for her right to speak. Gregory said he didn’t give a fuck what John Sampas, Viking Penguin, or anybody else thought of his supporting Jan Kerouac. She was his friend’s daughter, and he wished to help her. After he’d signed the petition, he looked at me with an expression of sincere pain and said, “I wish I had done more for my own kids. That was where I fucked up the most in my life.”

There’s so much I could write, but I am just going to describe a night in November 1980, in San Francisco, when I had just turned 31 years old. I had only moved to the West Coast (from Chicago) a little over a year earlier, and I was still pretty much of a Midwestern greenhorn in the ways of the Beat world. One night in North Beach Gregory offered to educate me. He explained that the “tuition” was that I would have to pay for his food and drinks all night long (mercifully not for his drugs too, his favorite “Thai stick,” which he bought himself). When my money ran out, he warned, he would find new companionship. It sounded like a good deal. It was, and I got one of the fullest nights of “education” I will probably ever receive. Thankfully I was smart enough to go home afterward, stay up the rest of the night, and write down as much of it as I could remember in my journal.

Here are a few excerpts:

“Gregory Corso in front of the Café Puccini, in his grey pants, red suspenders, black ‘Oscar Wilde’s vest,’ brown khaki shirt, leather bomber jacket, which he says he got from his father, who’s still alive—his face is peeling—he’s smoking a joint of Thai stick—giving puffs of it along with golden tequila to a Yorkshire terrier tethered to a parking meter, ‘taking care of the dog, who was nervous,’ Gregory says—then he finds out it belongs to a beautiful woman in the Puccini in a red coat—he tries to make her, but her girl-friend comes in and ‘interrupts’ (as he complains) and they go out together … Gregory says he told her she was a bitch ‘because nobody does that to me … even if it’s a woman … manners are important.’ Inside, he says he wrote poetry for a while but now he’s stepped outside the role of the poet, he’s just living—he’s quoting all his poems to me, the new ones: ‘I’ll star throw no more—tomorrow I’ll close the door—like an act of Jesus.’ [author’s note: Gregory later worked this into one of his published poems, as he often did with lines that he tried out in cafes and bars.]

“Gregory says the hardest thing for him to accept was the coming death of his children—he read some poem about having thrown out God, love, religion, all other grand concepts, but death was hiding under the sink—so he threw out death and the sink too—he said, ‘My humor saved me.’

On the way to the Caffe Sport, he wanted me to buy him a dinner. I say, ‘I love you, Gregory!’ Him: ‘Love nothing.’ Me, yelling, ‘Come on, Gregory! You can’t say that!’ Him: ‘So feed me, then! What kind of love is this if you won’t feed me?’

“The Caffe Sport was too expensive. I ended up buying him dinner at Little Joe’s on Broadway. The waitress got pissed off that he kept drinking out of his bottle of tequila there. ‘What is that, Gregory?’ she asked petulantly when he pulled out the bottle again. He responded: ‘Ichor, the blood of the gods.’

On the street again he says, ‘Most of these people are dead—they’ll never wake up.’ Later he tells me he’s getting tired of people turning away from him—he’s ‘disappointed in human beings … I open the door and they don’t come in … they’re gonna die … I’m alive, I’m not gonna die … they’re dead already.’

“I said I wasn’t good enough to write one-line Blakean apocalyptic verses like him. He said, ‘You been writing since you were eight, you’ll get there’—he’d said he was all alone in his room and started writing at eight—I told him I’d done the same thing. ‘Now you’re waking up, but when I first met you, you were asleep,’ he said. ‘No, just dozing,’ I replied. ‘Dozing’s dangerous,’ he said. ‘I don’t doze … you gotta be awake all the time … you want to get married, raise a family, you gotta keep your eyes open all the time. People think I’m a dumb drunk … I take care my kids, I know what’s goin’ on all the time … I do everything delicato.’ He gestures with gentle turn of his wrist.

“At the Puccini he shows me clippings from the New York Times about his participation in the poetry Olympics in Westminster Abbey. He says the article says he won. Later I get a close look at it, and it actually says they ‘applauded enthusiastically.’ But it did give his picture, and he was the only poet they quoted … it said he was leaning against a statue of Shakespeare and they asked him whether the Olympics were necessary to revive poetry—he said, ‘I don’t know whether we really need to help poetry, you see, poetry’s been around for a long, long time.’ I ask, ‘Did they know you were putting them on?’ ‘You bet they did! They loved me!’

“He tells me that spirit is individualistic and that’s why it’s beautiful. ‘If you die thinking it’s all going to go on after you when you’re gone, you’re all wrong, you lose, but if you think that when you die everything else is gonna go too, and something entirely new is gonna be born, then you got it, then you’ll never die.’ He quotes: ‘We don’t bewail the dinosaurs, and that’s no joke!’ He said he starts with the sunset and proceeds to the sunrise—most people make the mistake of starting with the sunrise and following it to the sunset—that’s how they see life.’

“Gregory told the Italian bartender at Dante’s that he’d come back that night with a pistole, an Italian name brand—I think it was a Rosco. They said, ‘We got plenty of pistoli.’ He told me they were dumb, they thought he was talking about real guns and violence. He said he was talking about ‘the pistol of my mind … the hot lead inside me … I don’t believe in violence … I’m not gonna shed any blood … I got a Rosco!’”

You get the idea. The magic of Gregory was always in the wild, inventive things he never stopped saying, and in the way he made what would otherwise have been ordinary dead time into an enchanted kingdom of marvels that only he could see, and that he would let you see too, if you were willing to pay the price of his always demanding company. It was worth it, every dollar, every hurt feeling, every bother he ever created. Like a few thousand other people, I miss him terribly.

Pax vobiscum, you lost child and fallen angel. You are now a shining star in the heavens, as we always suspected.

Gregory often pretended to be mean; and sometimes, drunk on vodka, he could truly be one of the meanest people you ever met. If you had a big nose, he could (drunk on vodka) spend an hour finding 5,000 brilliant poetic ways to make fun of your big nose. I have seen many people, men and women, leave a room in tears because they could not bear Gregory’s relentless, incisive jabbing at all their weak points. The more he saw you were hurting, the more he’d keep after you—till he got a response, the response he wanted. If you simply came back and said, “Aw Gregory, you’re just full of shit,” he’d probably smile and leave you alone for the rest of the night—depending on how much vodka he’d drunk. There were some nights when he simply wouldn’t quit, when a kind of animal anger in him just kept burning at white hot heat, and those nights it was better to leave him alone. The next morning he’d be all smiles, ask you to have coffee with him, and by the way, could you lend him twenty dollars?

But there was a big, real heart inside Gregory Corso. In the things that mattered, he did not fool around. I will never forget that when Jan Kerouac was banned from speaking at NYU in 1995, at a conference about her own father (Jack Kerouac), because the Sampases had cut a deal with Helen Kelly, the NYU programs director, almost all the Beats turned their backs on her. It was simple: Sampas had (still has) a major connection with Viking Penguin, where most of the Beats were or wanted to get published. A petition went round for Jan’s right to speak at the conference, but most of the Beats wouldn’t touch it, fearing to lose their upcoming Viking Penguin contract. Gregory Corso (along with Ed Sanders) was the only Beat who signed for her right to speak. Gregory said he didn’t give a fuck what John Sampas, Viking Penguin, or anybody else thought of his supporting Jan Kerouac. She was his friend’s daughter, and he wished to help her. After he’d signed the petition, he looked at me with an expression of sincere pain and said, “I wish I had done more for my own kids. That was where I fucked up the most in my life.”

There’s so much I could write, but I am just going to describe a night in November 1980, in San Francisco, when I had just turned 31 years old. I had only moved to the West Coast (from Chicago) a little over a year earlier, and I was still pretty much of a Midwestern greenhorn in the ways of the Beat world. One night in North Beach Gregory offered to educate me. He explained that the “tuition” was that I would have to pay for his food and drinks all night long (mercifully not for his drugs too, his favorite “Thai stick,” which he bought himself). When my money ran out, he warned, he would find new companionship. It sounded like a good deal. It was, and I got one of the fullest nights of “education” I will probably ever receive. Thankfully I was smart enough to go home afterward, stay up the rest of the night, and write down as much of it as I could remember in my journal.

Here are a few excerpts:

“Gregory Corso in front of the Café Puccini, in his grey pants, red suspenders, black ‘Oscar Wilde’s vest,’ brown khaki shirt, leather bomber jacket, which he says he got from his father, who’s still alive—his face is peeling—he’s smoking a joint of Thai stick—giving puffs of it along with golden tequila to a Yorkshire terrier tethered to a parking meter, ‘taking care of the dog, who was nervous,’ Gregory says—then he finds out it belongs to a beautiful woman in the Puccini in a red coat—he tries to make her, but her girl-friend comes in and ‘interrupts’ (as he complains) and they go out together … Gregory says he told her she was a bitch ‘because nobody does that to me … even if it’s a woman … manners are important.’ Inside, he says he wrote poetry for a while but now he’s stepped outside the role of the poet, he’s just living—he’s quoting all his poems to me, the new ones: ‘I’ll star throw no more—tomorrow I’ll close the door—like an act of Jesus.’ [author’s note: Gregory later worked this into one of his published poems, as he often did with lines that he tried out in cafes and bars.]

“Gregory says the hardest thing for him to accept was the coming death of his children—he read some poem about having thrown out God, love, religion, all other grand concepts, but death was hiding under the sink—so he threw out death and the sink too—he said, ‘My humor saved me.’

On the way to the Caffe Sport, he wanted me to buy him a dinner. I say, ‘I love you, Gregory!’ Him: ‘Love nothing.’ Me, yelling, ‘Come on, Gregory! You can’t say that!’ Him: ‘So feed me, then! What kind of love is this if you won’t feed me?’

“The Caffe Sport was too expensive. I ended up buying him dinner at Little Joe’s on Broadway. The waitress got pissed off that he kept drinking out of his bottle of tequila there. ‘What is that, Gregory?’ she asked petulantly when he pulled out the bottle again. He responded: ‘Ichor, the blood of the gods.’

On the street again he says, ‘Most of these people are dead—they’ll never wake up.’ Later he tells me he’s getting tired of people turning away from him—he’s ‘disappointed in human beings … I open the door and they don’t come in … they’re gonna die … I’m alive, I’m not gonna die … they’re dead already.’

“I said I wasn’t good enough to write one-line Blakean apocalyptic verses like him. He said, ‘You been writing since you were eight, you’ll get there’—he’d said he was all alone in his room and started writing at eight—I told him I’d done the same thing. ‘Now you’re waking up, but when I first met you, you were asleep,’ he said. ‘No, just dozing,’ I replied. ‘Dozing’s dangerous,’ he said. ‘I don’t doze … you gotta be awake all the time … you want to get married, raise a family, you gotta keep your eyes open all the time. People think I’m a dumb drunk … I take care my kids, I know what’s goin’ on all the time … I do everything delicato.’ He gestures with gentle turn of his wrist.

“At the Puccini he shows me clippings from the New York Times about his participation in the poetry Olympics in Westminster Abbey. He says the article says he won. Later I get a close look at it, and it actually says they ‘applauded enthusiastically.’ But it did give his picture, and he was the only poet they quoted … it said he was leaning against a statue of Shakespeare and they asked him whether the Olympics were necessary to revive poetry—he said, ‘I don’t know whether we really need to help poetry, you see, poetry’s been around for a long, long time.’ I ask, ‘Did they know you were putting them on?’ ‘You bet they did! They loved me!’

“He tells me that spirit is individualistic and that’s why it’s beautiful. ‘If you die thinking it’s all going to go on after you when you’re gone, you’re all wrong, you lose, but if you think that when you die everything else is gonna go too, and something entirely new is gonna be born, then you got it, then you’ll never die.’ He quotes: ‘We don’t bewail the dinosaurs, and that’s no joke!’ He said he starts with the sunset and proceeds to the sunrise—most people make the mistake of starting with the sunrise and following it to the sunset—that’s how they see life.’

“Gregory told the Italian bartender at Dante’s that he’d come back that night with a pistole, an Italian name brand—I think it was a Rosco. They said, ‘We got plenty of pistoli.’ He told me they were dumb, they thought he was talking about real guns and violence. He said he was talking about ‘the pistol of my mind … the hot lead inside me … I don’t believe in violence … I’m not gonna shed any blood … I got a Rosco!’”

You get the idea. The magic of Gregory was always in the wild, inventive things he never stopped saying, and in the way he made what would otherwise have been ordinary dead time into an enchanted kingdom of marvels that only he could see, and that he would let you see too, if you were willing to pay the price of his always demanding company. It was worth it, every dollar, every hurt feeling, every bother he ever created. Like a few thousand other people, I miss him terribly.

Pax vobiscum, you lost child and fallen angel. You are now a shining star in the heavens, as we always suspected.

Saturday, March 13, 2010

On 8/8/06, Madeline Kripke wrote:

“Angel”?

I was a Barnard College freshman in New York City in 1961, soon to become an English major. I’d come straight from a sheltered life in a kosher home in a small Midwestern town--to the Big Bad City. It didn’t take me long to feel both homesick and rebellious, and one wintry day, acting on both feelings, I set out for the Big Bad Greenwich Village: I’d go get a “kosher style” hot dog and a beer, and then I’d go check out the “scene.”

I took the downtown IRT to Sheridan Square and walked east to the Nedicks on 8th St. between 5th and 6th. I went in, ordered the objects of my desire, and sat there eating and drinking, feeling nicely content. At one point I looked up and saw a man in a dingy coat lurching his way inside, with his arm outstretched, and holding a snowball in his hand. He approached the counterman and asked if he could trade the snowball for a bowl of soup. As the counterman screwed up his face and made shooing gestures, I stared at the strange, lurching man, impressed with the originality of his come-on. He saw me staring at him and took a step or two in my direction. He looked at me just a bit beseechingly; and thinking he looked hungry, I invited him to sit down and share my meal. I cut the remaining piece of hot dog in two and poured half of my beer into an empty water glass.

After a few minutes of food, drink, and chit-chat he asked me if I knew who he was, and I said no. He told me he was Gregory Corso. At that point in my life I’d already read Gregory’s poetry; but I played it cool, betraying no hint of alarm. I though to myself: This is interesting. Either he IS Gregory Corso, in which case this is interesting, or he’s NOT Gregory Corso, in which case he has interesting delusions. So “Gregory Corso” and I talked some more, mostly, as it turned out, about poetry. He kept calling me his “angel.”

After we finished our partial meals, we got up to leave, and he asked me, or urged me, really, to walk him around for a while. I’d gathered he wasn’t feeling well, and I’d noticed a hospital tag around his wrist, so I decided to walk with him. We walked and talked, making our way through the snow back toward Sheridan Square. To my distress, my boots were leaky, and my feet were getting wet.

At “Gregory’s” suggestion, we stopped in a paperback bookstore half a block from the Square so I could buy a book of his which he would then sign for me. I bought The Happy Birthday of Death, and a while later he signed it. When we got to the Square he asked me what we should do next.

I looked around, and looked up, and being a kid from the Midwest, I said, “Let’s go bowling.” So we went to the bowling alley upstairs on the southwest side of the Square and played a couple of games. He won them fair and square, and I was relieved that I didn’t have to let him win. Before we left, he inscribed the book to me: “For Mad-- my angel bowler-- love, Gregory”

Then he asked me to walk him a couple of blocks north, to a bar. When we got there and went inside, two or three people yelled out, “Gregory!” and one came over and hugged him, saying, “I didn’t know you were back!” So he really WAS Gregory Corso!--just back from a trip to India.

After a while I left him with his buddies. He asked for my phone number and we made plans to meet again.

We did meet again—several times. I remember walking with him hand in hand through the Village, over a period of months, into the Spring, talking innocently and earnestly--and intelligently--about poetry. He offered to buy me new boots, but, of course, he never did, and I was disappointed. I quickly caught on that he’d boast of generous intentions and then fail to deliver. That was annoying, but it didn’t matter. He was always fun to be with, and he was always courteous to me. Back then, I was 18 and a bit of a morsel, but he behaved like a perfect gentleman. I was impressed with him for that. I knew he was married, and he never made an unwanted move on me.

Some 35 or 40 years later I came to know Gregory again through friends. He remained thoughtful, interested, and intriguing.

He never seemed to recognize me as his “angel bowler,” and I never brought it up to him. I must have been afraid he wouldn’t remember. Maybe I should have spoken up.

**

I am Huncke's literary executor. Roger is now dead but his wife

Irvyne is alive and I can ask for more specifics.

One thing I do remember when I was with my son in Roger's used book

store called the Rare Book Room -- Huncke was there, Roger, Gregory,

James Rasin, myself -- many people -- maybe Marty Matz, I'm not sure

if he was in town that day or not -- in any case my son was about 20

months old -- good looking face, very open with everyone -- good grass

and good whiskey -- anything anybody would have wanted was there

including great literature -- and when Corso met my boy for the first

time he picked up a magic marker and wrote YES across his forehead.

Later in the afternon turned to evening he did a portrait of my son on

the back of a letter off of Rodger's desk and I still have the

drawing.

All the best,

Jerome Poynton

**

Memories of Gregory Corso

By Gerald Nicosia

I knew Gregory Corso over a 24 year period, and have so many memories that sometimes I think I should write a book about him. In fact, Gregory was always mad that I had written Kerouac’s biography and not his. He used to say in his Greenwich Village bad boy’s voice: “I got one thing against you, man … you went for the dead one, man. You didn’t come for the living one”—meaning himself.

Gregory often pretended to be mean; and sometimes, drunk on vodka, he could truly be one of the meanest people you ever met. If you had a big nose, he could (drunk on vodka) spend an hour finding 5,000 brilliant poetic ways to make fun of your big nose. I have seen many people, men and women, leave a room in tears because they could not bear Gregory’s relentless, incisive jabbing at all their weak points. The more he saw you were hurting, the more he’d keep after you—till he got a response, the response he wanted. If you simply came back and said, “Aw Gregory, you’re just full of shit,” he’d probably smile and leave you alone for the rest of the night—depending on how much vodka he’d drunk. There were some nights when he simply wouldn’t quit, when a kind of animal anger in him just kept burning at white hot heat, and those nights it was better to leave him alone. The next morning he’d be all smiles, ask you to have coffee with him, and by the way, could you lend him twenty dollars?

But there was a big, real heart inside Gregory Corso. In the things that mattered, he did not fool around. I will never forget that when Jan Kerouac was banned from speaking at NYU in 1995, at a conference about her own father (Jack Kerouac), because the Sampases had cut a deal with Helen Kelly, the NYU programs director, almost all the Beats turned their backs on her. It was simple: Sampas had (still has) a major connection with Viking Penguin, where most of the Beats were or wanted to get published. A petition went round for Jan’s right to speak at the conference, but most of the Beats wouldn’t touch it, fearing to lose their upcoming Viking Penguin contract. Gregory Corso (along with Ed Sanders) was the only Beat who signed for her right to speak. Gregory said he didn’t give a fuck what John Sampas, Viking Penguin, or anybody else thought of his supporting Jan Kerouac. She was his friend’s daughter, and he wished to help her. After he’d signed the petition, he looked at me with an expression of sincere pain and said, “I wish I had done more for my own kids. That was where I fucked up the most in my life.”

There’s so much I could write, but I am just going to describe a night in November 1980, in San Francisco, when I had just turned 31 years old. I had only moved to the West Coast (from Chicago) a little over a year earlier, and I was still pretty much of a Midwestern greenhorn in the ways of the Beat world. One night in North Beach Gregory offered to educate me. He explained that the “tuition” was that I would have to pay for his food and drinks all night long (mercifully not for his drugs too, his favorite “Thai stick,” which he bought himself). When my money ran out, he warned, he would find new companionship. It sounded like a good deal. It was, and I got one of the fullest nights of “education” I will probably ever receive. Thankfully I was smart enough to go home afterward, stay up the rest of the night, and write down as much of it as I could remember in my journal.

Here are a few excerpts:

“Gregory Corso in front of the Café Puccini, in his grey pants, red suspenders, black ‘Oscar Wilde’s vest,’ brown khaki shirt, leather bomber jacket, which he says he got from his father, who’s still alive—his face is peeling—he’s smoking a joint of Thai stick—giving puffs of it along with golden tequila to a Yorkshire terrier tethered to a parking meter, ‘taking care of the dog, who was nervous,’ Gregory says—then he finds out it belongs to a beautiful woman in the Puccini in a red coat—he tries to make her, but her girl-friend comes in and ‘interrupts’ (as he complains) and they go out together … Gregory says he told her she was a bitch ‘because nobody does that to me … even if it’s a woman … manners are important.’ Inside, he says he wrote poetry for a while but now he’s stepped outside the role of the poet, he’s just living—he’s quoting all his poems to me, the new ones: ‘I’ll star throw no more—tomorrow I’ll close the door—like an act of Jesus.’ [author’s note: Gregory later worked this into one of his published poems, as he often did with lines that he tried out in cafes and bars.]

“Gregory says the hardest thing for him to accept was the coming death of his children—he read some poem about having thrown out God, love, religion, all other grand concepts, but death was hiding under the sink—so he threw out death and the sink too—he said, ‘My humor saved me.’

On the way to the Caffe Sport, he wanted me to buy him a dinner. I say, ‘I love you, Gregory!’ Him: ‘Love nothing.’ Me, yelling, ‘Come on, Gregory! You can’t say that!’ Him: ‘So feed me, then! What kind of love is this if you won’t feed me?’

“The Caffe Sport was too expensive. I ended up buying him dinner at Little Joe’s on Broadway. The waitress got pissed off that he kept drinking out of his bottle of tequila there. ‘What is that, Gregory?’ she asked petulantly when he pulled out the bottle again. He responded: ‘Ichor, the blood of the gods.’

On the street again he says, ‘Most of these people are dead—they’ll never wake up.’ Later he tells me he’s getting tired of people turning away from him—he’s ‘disappointed in human beings … I open the door and they don’t come in … they’re gonna die … I’m alive, I’m not gonna die … they’re dead already.’

“I said I wasn’t good enough to write one-line Blakean apocalyptic verses like him. He said, ‘You been writing since you were eight, you’ll get there’—he’d said he was all alone in his room and started writing at eight—I told him I’d done the same thing. ‘Now you’re waking up, but when I first met you, you were asleep,’ he said. ‘No, just dozing,’ I replied. ‘Dozing’s dangerous,’ he said. ‘I don’t doze … you gotta be awake all the time … you want to get married, raise a family, you gotta keep your eyes open all the time. People think I’m a dumb drunk … I take care my kids, I know what’s goin’ on all the time … I do everything delicato.’ He gestures with gentle turn of his wrist.

“At the Puccini he shows me clippings from the New York Times about his participation in the poetry Olympics in Westminster Abbey. He says the article says he won. Later I get a close look at it, and it actually says they ‘applauded enthusiastically.’ But it did give his picture, and he was the only poet they quoted … it said he was leaning against a statue of Shakespeare and they asked him whether the Olympics were necessary to revive poetry—he said, ‘I don’t know whether we really need to help poetry, you see, poetry’s been around for a long, long time.’ I ask, ‘Did they know you were putting them on?’ ‘You bet they did! They loved me!’

“He tells me that spirit is individualistic and that’s why it’s beautiful. ‘If you die thinking it’s all going to go on after you when you’re gone, you’re all wrong, you lose, but if you think that when you die everything else is gonna go too, and something entirely new is gonna be born, then you got it, then you’ll never die.’ He quotes: ‘We don’t bewail the dinosaurs, and that’s no joke!’ He said he starts with the sunset and proceeds to the sunrise—most people make the mistake of starting with the sunrise and following it to the sunset—that’s how they see life.’

“Gregory told the Italian bartender at Dante’s that he’d come back that night with a pistole, an Italian name brand—I think it was a Rosco. They said, ‘We got plenty of pistoli.’ He told me they were dumb, they thought he was talking about real guns and violence. He said he was talking about ‘the pistol of my mind … the hot lead inside me … I don’t believe in violence … I’m not gonna shed any blood … I got a Rosco!’”

You get the idea. The magic of Gregory was always in the wild, inventive things he never stopped saying, and in the way he made what would otherwise have been ordinary dead time into an enchanted kingdom of marvels that only he could see, and that he would let you see too, if you were willing to pay the price of his always demanding company. It was worth it, every dollar, every hurt feeling, every bother he ever created. Like a few thousand other people, I miss him terribly.

Pax vobiscum, you lost child and fallen angel. You are now a shining star in the heavens, as we always suspected.

**

I wrote the 13th Street piece in August, 1997 in New York City.

Regarding the infamous birthday party episode,

that would have been 1977, in Brigid Murnaghan's apartment on Bleecker St.,NYC.

(I corrected a typo in the eighth paragraph, section one: Gregory told me...

Mary Shanley: I have been publishing my poetry since 1984 and have enjoyed reading

and performing around New York City for the last twenty years.

Peace,

Mary

Shanley/Genet

lesdeux@earthlink.net

Pray for Peace WORLDWIDE!

On 8/20/06, Shanley/Genet wrote:

Kirby,

I read this piece at Gregory's memorial. Feel free

to use however much or little as you wish.

Best,

Mary Shanley

Gregory Corso Thirteenth Street Revisited

1.

Rolling nickels, dimes and quarters on the living room floor

then the short walk to the bank to deposit the coins

in a savings account marked, Vacation.

Crossing Thirteenth Street, I stopped short, having caught

A glimpse of a man who bore an eerie resemblance

To Allen Ginsberg. He was older, with grew hair and beard,

Wearing jeans, white button down collar shirt and tie

With a Rollieflex camera around his neck.

Just like Allen.

I lower my head, say a fast prayer,

“Rest in Peace, Allen,”

And looking up, Gregory Corso is walking

Straight towards me.

In a navy blue raincoat, his large belly protruding

Wearing narrow reading glasses at the tip of his nose

And looking, generally speaking, very well.

“Holy Shit Gregory,” say I, “I thought I just saw Allen

And now, here you are!”

His eyes got all wide and he starts with the, “WOW man,

Really!!!!

Holy Shit

What’dya know about that!!!

WOW! Far out, man.”

“Yeah man,” I agreed,

It was very far out.

Allen died two months ago.

I saw Gregory at the Shambala Memorial,

Where he was one of the last to speak.

Everybody was wondering where Gregory was.

Would he do a no show today, of all days?

But when he arrived, he spoke lovingly

of his lifelong friend, who stuck with him

through more thick than thin.

Gregory to me he finally began to have dreams

About Allen. “Did you feel like he was visiting you,

Gregory?” “Yes. He did visit me, but it wasn’t like

Those dreams I had after Kerouac died. Man,

Those dreams were crazy. Tense. Made me very edgy.

But Allen’s dreams were beautiful.

Calm and Clear.”

Gregory looks down,

Sad faced, lost poet.

“I’m the last one now.”

“Plimpton keeps trying to get an interview with me.”

“So, why don’t you give him one?”

“Yeah, I probably wouldn’t mind,

If he’d just keep the interview to poetry,

Not gossip.” He asked if I would go uptown

With him to Plimpton’s for the interview.

“When’s it happening?”

“Wednesday.”

“That’s tomorrow, Gregory.”

“Oh yeah, right.

The interview is tomorrow.”

“Sorry Gregory, I gotta work.”

“Get someone else to go with you.

You have to give this interview,

Gregory, it’s very important.”

He just shook his head.

2.

I reminded Gregory of how I’d first met him

Twenty years ago at Brigid Murnaghan’s apartment.

It was Brigid’s daughter, Annie’s birthday party,

And you, Annie’s Godfather arrived with

Michael J. Pollard.

“Oh Shit,” says Gregory.

“Yeah shit,” says I.

“We were all pretty fucked up then.”

“Yeah Gregory, but Pollard was the biggest

Pain in the ass with his Woody Guthrie records.

Every time someone new arrived at the party,

He would take them hostage and make

them listen to a Woody Guthrie record.

It was always the same song.

Damn annoying. Must have had to listen to

It at least twenty times that night.”

We both laugh.

“And then you! Jerking off in the living room

And walking around with the cum in your hand,

Like you didn’t have a clue what to do with it.

Brigid finally told you,”Throw the fucking scum

Down the toilet, for crissakes.”

“Oh shit. I did that?”

“You did that all the time, Gregory.”

A page of Beat History.

Gregory suddenly freaks!

“Oh my God! ..is Brigid still??

“Yes, Gregory, Brigid is still alive.

Gregory is relieved.

“Is she still down there at the Back Fence?”

“Yup.”

I gotta go see her.

I gotta go see Brigid.”

Gregory starts talking about Allen again.

“Maybe he loved me too much.”

But then he added with a chuckle,

“Allen was like a Jewish Grandmother.”

“You still writing, Gregory?”

He dodged a bit.

“Well I’m slow.

Every ten years I come out with something."

“You know what my favorite line is,” Gregory asks.

“It’s from Richard the Third,

Oh that I would die, to see no more death.

That really gets them when I say that line…”

Mary Shanley

New York City

This remembrance was first published

In Long Shot, Volume 24.

**

Dear Kirby Olson, as per an email from Eliot Katz, July 30th. Wanda Coleman

Copyright © 2006 for Wanda Coleman: For the purposes of internet

transmission, all rights to the material below are reserved during

electronic transfer for the author, who is transmitting it to the agent,

editor or publisher for which it was written and contracted. It may not be

used, reproduced, recorded or otherwise stored in a retrieval system without

written permission of the author or party to whom this transmission is

directed.

RE: GREGORY CORSO

Up from Los Angeles, on a late November afternoon in 1981, we cruised the

coast in Bruno, our tore-down 1968 Buick Skylark. Exhausted, we spent the

night in the forest home of a gracious friend. The next morning, my husband

Austin Straus and I snaked into Santa Cruz and miraculously scored the last

room available at the St. George Hotel. All the Beats were staying there,

partying in "headquarters"—Ferlinghetti's room. It would last a mere 48

hours, but it was the beginning of terminal night for poetry as we admired

it then. The last of the Beats, the soul-wrenchers, the delusional

illusionists and the glory seekers had gathered. I couldn't think of a

better birthday present than being featured among newcomers, like Kathy

Acker, at the Santa Cruz Poetry Festival, the 13th and 14th. Jerry Kamstra

and F.A. Nettelbeck had been central to the crew of Those Responsible.

Roaming around the festival site, a school auditorium that seated

six-hundred, I did what blissed-out smile-weary neophytes usually do: kissed

foreheads, shook the hands of legend after legend (Ginsberg, Kaufman,

Everson, I. Reed, et al.) and stammered that I was thrilled to meet them,

and timidly passed on a concealed copy of my 1977 chapbook at least twice.

As I was giving Jerome Rothenberg the stammering treatment, Gregory Corso

was stepping past. Rothenberg reached out, grabbed him by the elbow and

steered him into my uh-uh-uh. (If around at such moments, Austin could

remember a book or poem title, like "Marriage", his favorite Corso poem. I

would simply go blank). We stood there as I attempted to collect myself,

thinking 'Mr. Corso sure looks pretty healthy, given the rumors.' I looked

at his arms for tracks and saw none. He patiently gave me the once over

while I tried to find my tongue. I didn't. He said politely "Nice meeting

you," and sailed on, leaving me face-to-face with an amused Jack Micheline.

Wanda Coleman/Los Angeles

Known at "The L.A. Blueswoman," Coleman's Bathwater Wine was winner of the

1999 Lenore Marshall Poetry Prize, and her Mercurochrome was a bronze-metal

finalist in the National Book Awards 2001; recent books include Ostinato

Vamps (2003), Wanda Coleman--Greatest Hits 1966-2003 (2004), and The Riot

Inside Me: More Trials & Tremors (2005).

Reply Forward Invite Wanda to Gmail

Kirby Olson

Dear Wanda, I liked this one a lot. So what does all the copyright stuff mean...

Aug 8

Wanda Coleman to me

More options Aug 8

Dear Kirby Olson,

Thanks, I'm glad you like the piece. The block of text in front of it is

simply my pro forma way of protecting my work since in the digital world

there is no such thing as privacy and anything one can transmit

electronically can be appropriated electronically. I was submitting the work

to you, so you are entitled to first rights as if I were submitting this via

regular mail. Feel free to handle your anthology as you want. Libraries

away. So we won't get rich, nothing new. A letter or note of acceptance is a

contract. Just keep me posted on what your final moves are, and see to it

that I get my contributor's copy when its ready. Good luck with your

project!

Wanda Coleman/Los Angeles

P.S.: Enjoy your laziness while it lasts.

>On 8/8/06, Wanda Coleman wrote:

>>

>>Dear Kirby Olson, as per an email from Eliot Katz, July 30th. Wanda

>>Coleman

>>

>>

>>Copyright (c) 2006 for Wanda Coleman: For the purposes of internet

**

On 7/31/06, Dennis Formento wrote:

a quote from Gregory, summer 83, Naropa...

*a quick course in corso*

"dat's da shot---

and a poet don't miss no shot

whether it's a shot in the arm

a shot of whiskey

or a poem"

--Dennis Formento

**

Corso anecdotes

The last time I saw Gregory Corso was in a liquor store at the corner of Columbus & Union in San Francisco. He and the clerk behind the counter were engaged in a furious tug of war over a credit card, which the clerk was attempting to wrest from Corso’s hands in order to cut it up. “I am Norman!” thundered Corso, to no avail. The clerk got the card & snipped it in twain to Corso’s howls. I exited quietly so as not to have to venture the words, “Hello, Gregory.”

Ron Silliman (incident in late 1980s)

**

____________________

Steve Dalachinsky

Gregory & me

Sales on the street were slow that week so I decided to take the

afternoon off to go to the Kerouac Conference at NYU to see all my heroes

in a panel discussion on the Beat Generation. One of the guest speakers

was hero # 1ish Gregory Corso who I had known slightly since I was a kid

and who remembered me favorably one minute or was nasty as hell the next

tho never once actually recalling my name..

The discussion lasted about 2 hours and was very down to earth and Corso

it seemed was neither in a bad mood nor drunk. When it ended the members

all dispersed and Corso rushed to the back and exited by himself. I

followed.

I caught up to him about ½ a block up La Guardia Place going south and

catching my breath said "Hey Gregory" how’s it going?" "Fine kid." He

returned. "I’m in a hurry tho gotta get somethin to eat and then gotta

make it up to Town Hall for a sound check for the gig tonight. You comin

to that?" Like the year before there was going to be a big reading and

music festival to celebrate Kerouac and the Beat Generation. "Uh I’d love

to Gregory except it’s a bit out of my budget." (Tickets were 25 bucks

and up.) Without looking at me he said, "No problem kid." And pulling a

scrap of paper out of his pocket he scribbled something handed it to me

and as he turned the corner said, "Just show this to them at the back

door and I’m sure they’ll let you in." "Thanks Gregory. I’ll see you

there." and stuffed the paper into my pocket.

After he left I pulled it out to examine it, as I anxiously unfolded the

paper, there in large simple letters were the words "Let this guy in."

> the day after 9/11

>

> on the near-deserted street

> the old poet declares

> "it's like a holiday"

**

Jim Feast

Gregory Corso Anecdote

On Thursday, May 21, 1994, as part of "The Beat Generation" conference at New York University, a reading was held at Town Hall, featuring Corso, Ginsberg, McClure, Ferlinghetti, Waldman, and other luminaries. It was billed as a chance to see "the greatest rebel writers in America," with tickets at $40 a pop.

At this point, it seemed to a number of writers that the Beat extravaganza had become a free-floating imprimatur, which, like a travelling windbag, could be attached to any business enterprise, no matter how shady. Here it was being used to front a vast publicity/branding campaign through which NYU touted itself as a college located in the heart of the historic arts haven of Greenwich Village, whose cultural catchet (the trustees hoped) would serve as a magnet for Beat-linked tuition money. The outrageousness of known Beat writers submitting to this charade was only matched two years later when at the exhibit, "Beat Culture and the New America," at the Whitney Museum, billboards and bus ads for the show made the name of the sponsor, AT&T, more than double the size of the name of the exhibit. Moreover, the opening of the show coincided with AT&T's laying off 60,000 employees, who (we joked) with their last pay envelope received a complimentary copy of On the Road. Again, the living Beats, including Corso, Ginsberg, Waldman, et al.., who attended the opening of the exhibit, had to avert their eyes from the bestowers of laurels as they passed into immortality.

However, to return to 1994, as it happened I found myself on that fateful night shoulder to shoulder with a bunch of disaffected milksops, known as the Unbearables, including Ron Kolm, Carol Wierzbicki, Mike Menser, Sparrow, Jill Rapaport, and others, who were all fed up with the corporate shilling of their erstwhile Beat idols, and had come to protest at the Town Hall reading, hassling and heckling the customers who queued up with $40 in hand. We wiggled signs saying things like "Poetry Shouldn't Be Air Conditioned" and "Beat Off."

The hip, well-to-do attendees cut our ragtag band a wide berth, but one intrepid passerby stalked boldly over. It was Corso. In his patented screechy voice, he chided us. "You're a bunch of losers. You're not writers. Could you write better than me?"

"Give us a sample," Sparrow yelled out.

Believe it or not, then and there, out on the sidewalk on an unseasonably hot May evening, Corso began to recite. I can't remember exactly what poem he gave us. It might have been:

Spirit

is life

it flows

through

You know the rest. Then he had the chutzpah to add, "You losers can't write like that."

Sparrow pushed to the front and recited in turn.

"Cat"

A cat says,

Me-you, me-you.

"What did I tell you?" Corso snarled. "Youse guys can't write." He stalked off.

The most amazing thing about this spontaneous poetry slam was that all the dowagers, ad executives and cool, downtown trendsetters who were trooping into the auditorium moved as far as they could from our contest, probably taking it for simply another instance of New York "street life."

There is a post script. In 1999, a documentary film called The Source appeared. Its purpose was to talk about the beneficial and empowering influence of the Beats on young writers. At its center occurs what must be one of the most peculiar pans in cinema history. Stationed in front of Town Hall before the Beat reading, the camera makes a 360 degree turn to take in the joyous, nay, adulatory, atmosphere of the audience as it waits to see its heroes. Yet, at one point in this deliciously long pan, the camera unaccountably speeds up, only to fall back to its dropsical pace immediately after passing a group of fans who are holding signs. The camera moves so quickly the signs remains a blur -- they probably contained testimony to their love for the Beats (the film audience will think) -- but what can be made out is that the group is being hassled by a half bent over, shabby wino, yelling into the wind.

**

Aaron Belz

Here's my anecdote:

In Spring 1994, I was taking a class at NYU called 'Craft of Poetry'. The teacher,

the inestimable Mr. Ginsberg, missed class one day and arranged for Corso to

substitute for him. Corso had been built up a lot in the course. He was probably the

poet Ginsberg had talked about most--we spent a whole class talking about "BOMB" and

the beauty of juxtaposition: "Impish death" and "BING BANG BONG BOOM bee bear

baboon." So when Corso showed up, we had high expectations indeed. He spent most of

the period reading--sort of mumbling--through books he had brought. No teaching or

application. Then, half-way through the classtime, he quietly put his books in his

satchel and stood up. He said "good day" to us in a most gentlemanly way, and walked

toward the door. I thought "It's okay, it's Corso. He can do what he likes." But a

few of my classmates didn't feel that way. Several started booing and one stood in

front of the door and said "The class period isn't over." He grumbled, hunched his

shoulders and walked back to the front of the room an continued to do what he had

been doing. Aaron Belz

**

San Francisco, New Year’s Eve 1982/83. Gregory, Sarah Manafee and I are drinking, celebrating, the usual ra-ra jazz, though perhaps we’re even looser than most people. At around 20 minutes to midnight we’re singing and otherwise carrying on in the middle of the street near the corner of Grant and Columbus, and we’re smoking pot. So the cops grab us. (And mind you, only a week earlier Gregory and Allen Ginsberg had visited with the mayor.) We protest (“Hey, it’s New Year’s Eve!”) but to no avail. We’re handcuffed (hands in front) and tossed into a paddy wagon. Gregory is thrown next to a big black guy who isn’t cuffed. Out of the blue, the guy ups and hits Gregory, pow! bam! I throw myself on the mad assailant and manage to hold him at bay. Gregory is shocked, as it all happened so fast; and, contrary to what some folks may think, Corso wasn’t in any way a tough guy. I stay between the two of them the whole ride, and the black dude is simply itching to hit Gregory again. When we get to the police station, they put us in different cells and Gregory they put together with, yeah, the black bruiser! So I start screaming at the jailor: “You’ve just put a famous poet in with some maniac who’s trying to kill him!” With which I am taken to a part of the cop shop where I can’t even keep track of what’s going on. ‘Surely this is a setup,’ I’m thinking. The next day they release me and I learn that Gregory has been badly beaten up and is in the hospital with a broken jaw. Later we try suing the city but the attempt falls apart.

by Roberto Valenza

**

Three Gregory Corso anecdotes

by EDDIE WOODS

Amsterdam, Holland, autumn of 1979. Gregory’s been invited to read at the Kosmos Meditation Center and asks me to meet him there. For some reason (intuition, I guess, since they’re already signed), I stuff a bunch of Corso books in my shoulder bag. Arrive to find a slightly tipsy Gregory rowing with the main organizer, guy named Paul. Paul’s saying Gregory can’t read because he’s too drunk. Gregory retorts, “I’ve been this drunk for 25 years. Fuck the reading, just give me my money.” Paul replies, “If you don’t read, you don’t get paid. Besides, I bet you don’t even have any poems with you. What’s in that bag?” Gregory opens his plastic carry bag. There’s a bottle of cognac and that’s it. “See!” says Paul. My turn. I unzip my shoulder bag, pull out the books and hand them to Gregory. “Now let him read, Paul.” Paul refuses. The other organizers concur. People start coming in to hear Gregory, but there’s no reading. An hour or so later, with most of the would-be audience milling around in the lobby, chatting, wondering, Gregory sits on one of the steps leading to the performance space above and starts reciting poems. Folks gather in close, listening avidly, while the huddled organizers watch warily from a distance. Reading goes on for well over an hour, at the end of which Gregory stands, walks down the steps and, facing Paul and his Kosmos cohorts, a freshly-lit cigarette stuck in his mouth, drops into a full lotus, hobnail boots and all. “You get the ball game?” he asks. They didn’t, of course, but finally someone decided they better pay him. Oh yeah, what no one knew (not even me till much later) is that Gregory was double-jointed.

This one I heard from someone who was there, witnessed it. Benn Posset, aka Soyo Benn, late impresario of international poetry events, who from 1978 till a year before his untimely death in 1994 brought hundreds of poets, prose writers, also musicians, from all over the world to Amsterdam, including to perform at his annual One World Poetry festivals. But this took place in New York, sometime in the mid-1980s. There’s this big do at a theater in Manhattan and the whole gang is in attendance: Burroughs, Huncke, Ginsberg, probably Giorno, et al. Only Gregory not. Gregory had recently got his paws on Ginsberg’s checkbook, written a check for a thousand bucks made payable to himself and forged Allen’s signature (years before, in Amsterdam, I’d seen him sign Ginsberg books with Allen’s name and you couldn’t tell the difference). Well, as soon as Allen found out, he stopped the check, in what he thought was good time. Intermission for whatever was happening inside, everyone’s standing out front in the evening air jaw-jawing. Suddenly along comes Gregory. Heads turn, eyes stare, because they all know the story. Gregory, looking almost cherubic, ambles up to Allen and falls down on his knees. What’s this, he’s going to beg forgiveness?! Instead Gregory reaches into his pocket, pulls out ten 100-hundred dollar notes and counts them onto the pavement. Then before anyone can move, especially Allen, scoops the bills back up, smiles a devilish chuckle and scurries off. Benn swore it was a true tale, and knowing Gregory I believe him.

This one I could either tell straight or simply quote from my memorial poem for Allen Ginsberg entitled “Amsterdam Kaddish.” Think I’ll opt for the latter. (The Kosmos reading referred to here, arranged by Soyo Benn, took place a few years after the one described above—which itself followed on the heels of a One World Poetry festival that Benn had flown Gregory over for.) I am saying all this to the departed Allen:

Or better yet, that grand reading at the Kosmos,

the one you never knew (not then, thank God) the whole truth about:

you, Peter, Steven Taylor and Mister Gregory ‘reincarnation of Catullus’

Corso,

his boozed-up smacked-out utterly disreputable self in lovable person.

And you told Gregory only days before either he straightened up PDQ or

shipped the hell out,

‘cause no way you would go on stage with him, the lyrical Beat brat of a

bard,

no damn way if he stayed in that condition.

Gregory straightened up, all right. Only on the very night it all went down,

he early on called out to me across the still-empty hall that would soon fill

to brimming,

called out with sweet pleading cold-turkey poise:

“Eddie O Eddie O Eddie O-ooooo!” And yes, Allen, I did indeed slip him the

ball of opium

that perhaps pulled all of you through that magnificent performance--

you “Howl”-ing with strong maturity of serene grey years,

Gregory winking his way along mischievous lines of the Marriage poem,

Peter sternly sounding off his good fucks with Denise & such...

from “Amsterdam Kaddish” by EDDIE WOODS

**

Kathleen Wood

Gregory

Gregory stumbled into the saloon.

He ordered a screwdriver.

I ordered a Beck’s.

We introduced ourselves.

He said he liked my hair.

He wanted to buy me dinner

At Baby Joe’s on Broadway.

We left the bar.

As we walked, he told me

All about his experiences

Fucking boys with Allen in Tangiers.

In the restaurant, we drank beer

And he told me he was

An ex-junkie and

An alcoholic and proud!

So very proud of it all.

He said everyone here gave him

A bad rap, but

Everyone loved him

In New York and

He would take me with him and

We’d stay at the Chelsea

Where Edie and Sid and Nancy stayed

And he would introduce me

To the most wonderful people.

And after we finished our pasta,

He asked me if we could go

To my place.

I said ok, but I lived

In a residential hotel and

He had to leave by 10 p.m.

We took a bus to Fourth and Mission

And traipsed through the ritzy lobby

Past the disapproving glare

Of the desk clerk.

Halfway up the stairs

Gregory decided we needed

Vodka. We turned around

And went next door to Merrill’s

Where we purchased a pint

Of vodka and a quart

Of orange juice.

As we paraded through the lobby

Gregory was swigging

From the vodka bottle.

Upstairs we drank screwdrivers

From the complimentary plastic cups.

He said he wanted to fuck me.

I said he had to use a rubber.

I handed him a package.

He said the grillwork

On my pseudo-Victorian bed

Would be perfect for bondage.

I gave him a few of my scarves.

I removed his shirt

I asked him why there were scars

All over his arms and chest.

He told me he’d been attacked

By an ocelot.

I stripped and he tied

My arms and legs

To the bedposts.

Then

He fucked me.

We went and got more vodka

When we returned, he asked me

If I’d ever read his poetry.

I said no, but I would

Read it later. He said

I really should because

It was very good.

I told him I wrote poetry too.

I showed him book

Of poems about punk rockers,

Junkies and coke fiends.

He told me it was good.

Then he said that he

Was a better poet than I was

Because he was a traditionalist.

I said I’d be sure

To read his book.

At five of ten, I told him

That he would have to go.

He said he was broke

And demanded ten dollars

For cab fare.

All I had was a twenty.

He told me he would take that.

His voice was getting

Louder by the second so

I gave it to him.

He left.

I was afraid he’d call me.

He never did.

A week later,

A friend of his told me

That Gregory was in New York

At the Chelsea where Edie lived.

I discovered he’d left

His watch in my room.

I took the watch to a pawn broker,

But the guy told me

He could only give me

A couple of bucks for it.

Kathleen Wood

from her book The Wino, the Junkie and the Lord,

Zeitgeist Press.

Kathleen was, at the time of this writing, an extraordinary young beauty.

This poem received c/o

Bruce Isaacson

Zeitgeist Press

327 Carlisle Crossing St.

Las Vegas, NV 89138

Phone: (702) 205-7100

Facsimile: (702) 507-0038

www.Zeitgeist-Press.com

**

Gregory Corso at Brooklyn College

On 4 March 1991, Allen Ginsberg brought Gregory Corso to read his poetry at Brooklyn College. Before the reading Corso talked to the audience about the Gulf War, which had just come to an end. He said he didn’t know how to feel about the war. Of course, he was proud to be an American. He had a natural pride in his homeland – the earth he was born in. He supposed it was right for a bigger guy to meddle in a fight with a smaller guy who was beating up on an even smaller guy. But our arrogance bothered him. He went on to read a selection of early, middle, and late poems.

Allen planned to take Gregory and Peter Orlovsky to lunch at the Campus Corner, a local restaurant, and he asked me to join them. Before long, Corso was up to his old tricks. On the way down in the elevator, he noticed an African-American couple standing in the rear. He immediately began: “Then I beat the shit out of those five black mothefuckers. They were begging for mercy….etc.” Ginsberg cringed but chuckled too. Turning to the couple, he said: “Don’t mind him. This is the drunken poet that read here today. He’s just trying to get a rise out of you.” He was also, of course, trying to embarrass Allen Ginsberg, Distinguished Professor. Luckily, the students, realizing they were being put on, took it well.

On the walk over to the Campus Corner, I began talking with Allen about Tom Clark’s biography of Charles Olson, which I had just finished reading. Being a librarian myself, I was very interested in a story Clark told about Corso being beaten up by a special collection’s librarian at Buffalo after Corso called him “a faggot.” Clark writes “…the angry librarian flattened the abusive poet with one punch.” (Charles Olson: The Allegory of a Poet’s Life. NY: W.W. Norton, 1991, 318) Corso admitted calling the librarian “a faggot” but added that the librarian had a student call him out of Olson’s class, then sucker-punched him, and broke his nose. He described Olson looming over him after the class, keeping ice packs on his bloody nose. A doctor wanted to re-set the nose but Corso said “fuck it, leave it the way it is.”

At the Campus Corner Corso continued to flirt with a young girl that came to the reading – pretty, dark-haired, Long Island girl, early twenties, “half Italian and half Jewish,” she said. “Ah! Half Jewish,” yells Gregory, “then it’s that shot – if your mother’s Jewish, then you’re all Jewish.” He went on to flirt with the waitress: “How would you like to be my future ex-girlfriend?” Not getting much of a response, he focused on a group of high school students in the next booth: “I’ll bet I could take those girls away from these guys.”

A few minutes later he noticed an older woman using an inhaler and he began to commiserate with her: “Asthma? Yea, I got it too.” But then starts to get raunchy. “It’s terrible. I had an attack like that while I was having sex with a woman in Italy. It’s hard to breathe. Really tough when you’re going to come…bla bla bla.” The woman and her female companion did their best to ignore him.

Corso turned to me and said: “You can tell I don’t get out much. I just want to have some fun. I wish I were alive!” He then turned back to the high school students and before long they were engaged in a lively conversation about sex, relationships, birth control, fellatio, sodomy etc. He had them rolling in the aisles. Before leaving, I asked the kids “How’d you like this guy for an English teacher?” “He’d probably molest all the young girls,” one of the boys answered. “Damned straight,” I thought.

Ginsberg and I walked back to the College, after Gregory, Peter, and company headed home to Manhattan. Ginsberg remarked: “He really gets through to the kids. Too bad we can’t have him here at Brooklyn College.” For once in my life I was speechless.

William M. Gargan

**

RADIO SÉANCE ENGINEER

In the mid-80’s I was at Naropa Institute’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, Colorado. I signed up to have a one-on-one with Gregory Corso, so he could read and critique a manuscript of mine. He told me to come to his apartment at the Varsity Townhouses the next day, the apartment complex where many students and teachers would live during the summer session. The meeting was set for 2pm and I was thrilled, anxious & fearful of what this icon of poetry would say & do to me & my ego. Here was one of my Beat Heroes who would be laying hands on my poetry. At 2pm I arrived at his apartment expecting some intimate one-on-one powwow & rather found myself in a noisy, smoky room of stoned, drunk poker players. Gregory was the dealer. He had a bottle of whiskey within easy reach and he was pretty smacked out, eyes half closed one minute then shouting and laughing the next. My manuscript was on the table, surrounded by cards, cigarette ashes, chips and pretzels. I started feeling sick and wondered how to get out of this. How could Gregory possibly edit my poem in these conditions, and in his condition? But, Gregory leaned out of the swirl of chaotic cackling and smoke, and like a magician waved his pen in the air and made incredible, precise, and artful cuts, then returned to the partying, then back to my poems, back and forth, in and out, until he finished the edits that set my poem in balance. In the end, it was definitely a better manuscript than what I brought him. Gregory knew his business and was no fool, though it might have been easy for many to jump to that conclusion based on the drunkenness and outrageous behavior that was going on outside of his brilliant center. But Gregory was a master. He knew how to locate the essentials within a poem. His ear for the line was so finely tuned, and he was so ecstatically focused, that nothing could interfere with his innate sensibilities and his craft. I will always be grateful for my experience of Gregory Corso and the great work and wisdom he has left.

Goodbye Gregory. – Michael Rothenberg

**

Dear Dr. Olson,

My fellow Unbearable, Jim Feast, forwarded me your message

soliciting

recollections of Gregory Corso. Here's mine:

I was not formally introduced to Corso. I was working at the

Poetry

Project's New Year's Day Poetry Marathon at St. Mark's Church in

New

York, I think it was around 1998. I was posted at the door along

with a

young woman, collecting money for the event. Suddenly Corso

walked in

from the performance room, ranting (from what I could hear)

about the

order of the readers. Apparently he was not happy with the

reader he

would have to follow. "Goddamn Poetry Project!" he muttered

under his

breath. "Goddamn Ed Friedman [the Poetry Project Director]!"

The young woman next to me obviously had no idea who this was.

"Oh

please, sir, don't say that about the Poetry Project!" she

pleaded

anxiously. I didn't want to interrupt him. I was just delighted

to see a

Beat icon and the author of one of my favorite poems (Marriage

Poem)

"performing" in true character.

Eventually Ed Friedman appeared, and ushered him back into the

performance space.

--Carol Wierzbicki, Editor, Unbearables anthology, "The Worst

Book I

Ever Read" (forthcoming)

**

Eliot Katz

Some Recollections of Gregory

The first time I ever saw Gregory Corso was at an infamous poetry reading at the St. Marks Poetry Project in New York City around 1976. Allen Ginsberg was reading with Robert Lowell, and St. Marks Church was packed with six or seven hundred people. There was an audible buzz in the chapel in anticipation of this interesting mix of leading poets from different schools of American verse. Out of respect for Lowell as the elder and as the one traveling from out of state, Ginsberg read first.

I was in my late teens at the time and had recently decided to try writing poetry after taking a class at Rutgers University on the Beat Tradition in American Literature. I'd read several books by Ginsberg and Kerouac, but only a few Corso poems, including "Marriage," that had been published in a recent Norton anthology. I'd come to the reading, as I recall, with my roommate and Beat Tradition classmate, Danny Shot (with whom I would later start Long Shot literary journal), and our Beat Tradition grad-student professor, Bob Campbell.

During Lowell's reading, he announced that he was going to read a new long poem about his hometown that he'd never read in public before. Again, one could hear a buzz among the many Lowell fans in the audience. During the poem, Lowell stopped several times to explain references, saying things like "this was the place in my hometown where we...." After about the third time Lowell did this, a loud voice rose from the otherwise silent audience: "This ain't a classroom, Lowell!" Most of the audience seemed shocked that anyone would yell in the middle of Lowell's poem. A few yelled back, "Shut up!" The Heckler Extraordinaire responded, "Don't tell me to shut up, I'm the poet-man!"

I can't remember whether it was Bob Campbell or someone else in the audience who told me that was Gregory Corso, but I quickly understood why Gregory had developed a reputation as a kind of trickster of the Beat Generation. A few minutes later, with Lowell continuing to read from his long poem, a child sitting with Gregory started crying and more people began asking aloud for Gregory to leave. Gregory's reply this time was: "my baby can cry, my baby can cry." When Allen from the stage finally asked Gregory if he would leave and meet Allen outside after the reading, Gregory asked politely "do I have to?" and left.

It's difficult to forget discovering a poet that way. Gregory had been rude, sure, but there was a fascinating quality to Gregory-as-provocateur, and I had guessed that Robert Lowell would easily shrug "ah, Gregory," and not worry too much about it. I remember going out pretty quickly to buy some of Gregory's books--Gasoline, The Happy Birthday of Death, Elegiac Feelings American, Long Live Man--and happily discovering poems filled with a similarly captivating and provocative spirit; a deep well of knowledge about myth, poetic tradition, and politics; a wildly inventive sense of phrasing; and an incomparable comic imagination. I also remember noticing, just a few years later, that Gregory had been removed from the next edition of the Norton anthology in which I'd originally read a sampling of his work--although I know previous poems are often deleted from these kinds of collections to make room for new poems, I always harbored a slight suspicion that his erasure from that edition was in retaliation for heckling Lowell that night.

I met Gregory in the early 1980s through Allen Ginsberg, with whom I'd studied at Naropa in the summer of 1980. It was either in the fall of 1980 or in 1981 that I worked to bring Allen and Gregory to do a reading together at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey. I got a little extra funding from a student activities board to have them do a small workshop in the late afternoon, a few hours before their larger reading at night. For his part of the workshop, Gregory talked about how Greek and Roman mythology had influenced his poetry. And he drew fast, intricate, improvisational diagrams on a blackboard showing the relationships between various mythological figures and between the Greek and Roman variants of his favorite gods and goddesses. It was like watching a skilled jazz musician at work using the instruments of voice and chalk. Gregory compared the role of the poet to Hermes or Mercury, society's messengers--bringing people information, images, dreams, and underground ideas they might not otherwise receive.

At the Rutgers reading that night, in a completely filled student-center auditorium that fit about 500, Allen and Gregory took turns reading poems. Allen read beautifully as always. And, with a number of influential professors in the audience, Allen seemed concerned with helping to make sure Gregory created a good impression as well. Allen suggested to Gregory a few times to read his most well-known poems like "Marriage" and "Power." Instead, Gregory read solely from his latest book, Herald of the Autochthonic Spirit. This was the first time I'd heard these poems--"Columbia U. Poesy Reading," "I Gave Away," "The Leaky Lifeboat Boys," "Many Have Fallen," "Getting to the Poem," "Feelings on Getting Older," "How Not to Die," "The Whole Mess...Almost"--and I?m guessing that was true for most people in the audience. I would later hear Gregory read about a dozen more times through the years, but I never heard him better than he was that night. He just blew the audience away. With poems full of explosive ideas, surprise phrasings, and stunning endings, it was clear what Emily Dickinson meant when she said that she could tell a poem was a great one if it made the top of her head feel like it was coming off.

I brought Gregory down to New Brunswick, NJ for two or three more poetry readings in subsequent years. One of those times was among my favorite readings that I've ever been able to be a part of, where I had the chance in April 1986 to open up for Allen and Gregory at Rutgers? Kirkpatrick Chapel. For Gregory, however, that was a difficult reading, as he'd come to town with pneumonia, and was only able to read a short set before stepping off the stage and into his car ride back to where he was staying that night above New Brunswick's Old York Bookstore.

Andy Clausen was one of Allen Ginsberg's favorite younger poets and an old friend of Gregory's. I'd met Andy during my first trip to Naropa, and he stayed with me in New Brunswick for about six months in the early 1980s during a period when he and his then-wife Linda were separated and soon after my then-girlfriend, Joanne, had moved out. One day, Andy called me from New York City at my print-shop job and surprised me by saying that Gregory was coming down to New Brunswick to hang out with us that night. We arranged to meet at The Melody Bar. When I got there, Andy and Gregory were outside of it, having just gotten kicked out by the bouncer, Big Mike, after Gregory had rolled a joint on the bar. Danny Shot and I had helped the Melody's new owners turn the bar into a popular hangout, so I was able to talk one of the owners into letting Gregory back in. Back at our apartment--I can't remember whether it was after we came back from the bar or the next day after Gregory had crashed on our floor--Andy showed Gregory a copy of the first issue of Long Shot literary journal, which Danny and I--with the help of a financial donation from Allen--had published about six months earlier. Gregory spent some time looking through it and really enjoyed it. Whereas Allen was a renowned supporter of small-press literary journals, I'd heard it could be difficult to get poems from Gregory if one didn't have any funds to offer. So I was happily surprised when Gregory generously asked if we'd like a poem from him for our second issue. When I said that, of course, we'd love one, Gregory sat down at my kitchen-table electric typewriter, pulled out a small pocket notebook, and typed out a piece he'd drafted in his notebook called "Delacroix Mural at St. Sulpice." About four lines from the bottom, Gregory stopped typing and asked me what I thought of his last three lines. I read the lines in his notebook and said that I liked them, but not quite as much as the rest of the poem. I thought he would either get mad at me, or perhaps make up three new lines on the spot. Instead, when he finished typing what had been the fourth-to-last line, he got up from the chair, waved his left hand suavely, and said that I was right and the poem was done. It was a beautiful ending--"I know the ways of god / by god!"--and a great lesson in ending a poem early, at a poignant line, rather than tacking on additional lines that might weaken the poem. In my mind, I pictured Gregory arriving at so many of his poems' powerful endings by using that same suave wave-of-the-hand motion. After getting up from his chair and giving me the typed page for Long Shot, he also tore out the poem's handwritten manuscript and gave it to me as a gift, which of course I still have.

I didn't know Gregory nearly as well as many others did, but he was always very friendly and charming with me. I think I hung out with him between a dozen and two dozen times in New York or San Francisco through the years. After a reading he did at The Museum of Modern Art in New York City, we had a long conversation about the last lines in his "Getting to the Poem": "I will live / and never know my death." I asked how he could be so sure what he would know or not know at the instant of death, and he gave me a pretty good answer. Once when I was visiting San Francisco, Gregory asked if I would give him $20 (which I guessed was for his fix, but I didn't ask) and, in return, he took me later that night to a rotating bar on the top floor of the Hyatt Hotel, where a friend of his bought us drinks. In New York City in the mid-90s, I was invited to be part of a morning photo shoot with Allen, Gregory, and two of Allen's favorite poets from the generation younger than me, Geoffrey Manaugh and David Greenberg. The photo was being taken by a well-known portrait photographer, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, for New York magazine, in conjunction with an upcoming Beat exhibit at the Whitney Museum. Gregory arrived late, and wasn't in the photo that was eventually published, but I remember how much he enjoyed the long leather jacket that Timothy Greenfield-Sanders had given him to wear for one set of photos. After the photo session, we walked to a local restaurant to have lunch and I took a photo of Allen and Gregory walking together in the street, both at that time still looking quite happy and healthy.